Varistem vs BlastBags™

Your choice of stemming plug is a significant decision for mining and blasting consumables. You might be fighting flyrock on sensitive benches, or trying to

With chemical energy still being one of the most cost-effective means to reduce the size of rock to liberate strategic minerals and metals, blasting activities play an integral part in mining and quarrying operations. Albeit, these activities can generate significant environmental impact, including noise pollution, nuisance and air overpressure (commonly referred to as airblast). Understanding the science behind the generation and impact of blast-induced airblast is the key to the implementation of appropriate mitigation measures to reduce, as far as reasonably practicable, the impacts of blasting activities. This article aims to shed light on the origins and impact of blast-induced noise, airblast and air overpressure, as well as strategies for effective management.

The first step to understanding airblast is to define common terms associated with airblast as this has been an area of common misconception. Although airblast and air overpressure are generally used interchangeably, there is a distinct difference between the two concepts. Airblast is the transient change in pressure (pressure wave) resulting from the detonation of an explosive that travels through the air at the local speed of sound, whereas overpressure refers to the peak positive pressure resulting from the airblast wave. Airblast is commonly associated with measurements done in decibels (dBL) and it is important to note that these measurements refer to noise readings and not the pressure of the airblast wave. The applied force from the pressure wave is the cause of structural response which may result in damage to surrounding structures, and the noise is mostly associated with the perception of the blast.

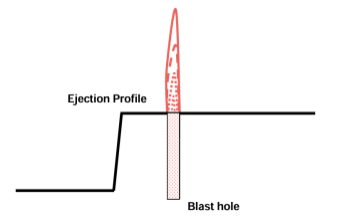

The main mechanisms associated with airblast generation from a blast are air pressure pulses, rock pressure pulses, stemming pressure pulses and gas release pulses. The level of airblast generated is also impacted by external factors such as weather conditions and direction due to the Doppler Effect. The following definitions have been derived from Du Pont (1977), Singh et al. (2005) and Schwartz (2016):

Blast-induced airblast is measured as a noise reading in decibels (dBL) through specialised microphones. The standard overpressure linear microphone (Figure 5) has a linear frequency weighting with a frequency range of 2Hz – 250Hz, a trigger level between 100dBL – 148dBL and an amplitude range of up to 500Pa (Instantel, 2025). There are various specialised microphones with different specifications and the type of product used will depend on site specifics. It is also vital that monitoring equipment be stationed appropriately and calibrated regularly to ensure accurate measurements. A blast monitoring setup usually includes a seismograph and an air overpressure microphone which is connected to a main box that records the readings (Figure 6).

An example of a blast monitoring report is indicated in Figure 7. The report typically includes the vibration data (Peak Particle Velocity or PPV measured in mm/s) as well as noise levels recorded (dBL) and the air overpressure (kPa) determined for the blast event recorded. These reports also indicate other valuable information such as:

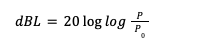

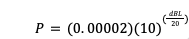

If overpressure is not indicated on the monitoring report, it can always be calculated from the noise readings to pressure using the following equation (Du Pont, 1977):

Equation 1:

Where:

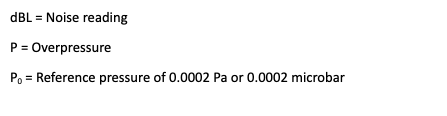

Therefore, the air overpressure (P) can be calculated by rewriting Equation 1:

Equation 2:

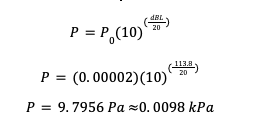

For example, considering the noise reading given in Figure 7 (i.e. 113.8dB), the equivalent calculated air overpressure is:

It is important to note that the number of holes or size of the blast block does not have a significant impact on the blast-induced airblast considering that a single poorly charged-, poorly stemmed- or incorrectly timed blasthole is sufficient to generate harmful airblast levels. The quality of design execution is, therefore, just as important as the design itself.

The main factors affecting the level of airblast generated from a blast include:

Atmospheric conditions can affect the intensity of noise levels recorded at a distance from a blast as these conditions determine the speed of sound in the surrounding air, at various altitudes. Temperature variations can cause an inversion layer – i.e. temperature and sound velocity increases with altitude. This inversion causes the refraction of ray paths towards the earth’s surface resulting in a slower decay of noise levels with distance and a potential intensity increase (of noise levels) by a factor of 2 to 3. The challenge with cloud cover is not that the bottom of clouds reflects noise waves (a common misconception), but rather that the clouds indicate the existence of an inversion layer. The clouds block the sunlight from heating the earth’s surface below which prevents the necessary heat build-up required to eliminate the temperature inversions (Du Pont, 1977).

The effects of temperature, amplitude and sound speed on the propagation of noise from a blast sire are depicted by the schematics, in Figure 10, Figure 11 and Figure 12. These visualisations capture just how important weather conditions are when blasting in sensitive areas.

In conditions with isothermal air and zero wind (Figure 10), a normal dissipation in noise propagation is seen with an increase in distance from the blast site. However, when an inversion is present, the speed of sound increases with temperature and altitude, giving a slower dissipation of noise levels with distance as indicated in Figure 11. This is generally the case in overcast conditions and may cause increased noise readings and a higher impact on the surrounding communities. It is for this reason that blasting is not recommended on days with high cloud coverage.

General good practice will be to avoid times in the day when cooler temperatures and inversion layers are probable, like early mornings and after sunset. The best blasting times in sensitive areas are therefore midday (indicated in Figure 12) when there is a decrease in sound seed and temperature with an increase in altitude resulting in ray paths that are refracted away from the earth’s surface and a rapid decrease in noise level with increasing distance. The added benefit of blasting midday is that most communities are busiest and noisiest during this time, which further assists in reducing the perception of the blast-induced noise experienced by the community.

The impact of blast-induced airblast can be subdivided into structural damage. Human perception and comfort and environmental impact.

Structural Damage: High-intensity airblast can cause structural damage to buildings, infrastructure, and equipment located near the blast site. The level of damage depends on various factors, including the distance from the blast, magnitude of overpressure, and structural integrity.

On 02 August 2024, the Chief Inspector of Mines (CIOM) issued the “Guideline for a Mandatory Code of Practice for Minimum Standards on Ground Vibrations, Noise, Air-blast and Flyrock near Surface Structures and Communities to be Protected” (DMRE, 2024), wherein the newly recommended South African standards for ground vibration and airblast are stated. Table 1 indicates the recommended South African standards for safe air-blast levels as found in the guideline DMRE 16/3/2/1-A8.

Table 1: Recommended air-blast levels at the structure that needs to be protected (DMRE 16/3/2/1-A8)

| Noise (dB) | Effect |

| 100.0 | Barely noticeable |

| 110.0 | Readily noticeable |

| 120.0 | Currently accepted by the South African authorities as being a reasonable level for public concern (not more of 10% of the measurements should exceed this value) |

| 134.0 | Currently accepted by the South African authorities that damage will not occur below this level (no measurement should exceed this value outside of the mine boundaries) |

| 164.0 | Window break |

| 176.0 | Plaster cracks |

| 180.0 | Structural damage |

Converting the same noise readings to the relevant overpressure (using Equation 2) gives the information in Table 2.

Table 2: Air-blast levels (DMRE 16/3/2/1-A8) and respective Overpressure levels and applicable effect

| Noise (dB) | Overpressure (kPa) | Effect |

| 100.0 | 0.0020 | Barely noticeable |

| 110.0 | 0.0063 | Readily noticeable |

| 120.0 | 0.0200 | Currently accepted by the South African authorities as being a reasonable level for public concern (not more of 10% of the measurements should exceed this value) |

| 134.0 | 0.1002 | Currently accepted by the South African authorities that damage will not occur below this level (no measurement should exceed this value outside of the mine boundaries) |

| 164.0 | 3.1698 | Window break |

| 176.0 | 12.6191 | Plaster cracks |

| 180.0 | 20.0000 | Structural damage |

On sites where there is no prescribed legal limit for blasting vibration and airblast, it is left to the experts in the field to set limits and measure and control vibration, noise and airblast. Most explosive- and mining companies have adopted the USBM guidelines:

Table 3: USBM guidelines for airblast damage levels

| Noise (dB) | Effect |

| 100.0 | Barely noticeable |

| 110.0 | Readily acceptable |

| 128.0 | Reasonable level of public concern (Max. 10% of measurements exceed this value.) |

| 134.0 | damage will not occur below this level (No readings should exceed this outside the mining boundary) |

| 150.0 | Single pane windows my break |

| 176.0 | Plaster cracks |

| 180.0 | Structural damage |

Human Perception and Comfort: Even at lower levels, airblast can be perceived as a loud noise, leading to annoyance, discomfort, and potential psychological stress for individuals residing or working in the vicinity of blasting activities. Mines and quarries have become cognisant that even though blasting is carried out safely and no physical harm or structural damages are incurred, the nuisance level perceived can still be high which leads to complaints and stricter guidelines. The perception from nearby communities forces mines and quarries to have rigorous QAQC policies and to make use of blast designs and products that mitigate the generation of airblast. This leads to higher operational costs and, to some extent, a loss in productivity and performance. Albeit, if the community is unhappy the reputation of the mine or quarry is at stake which may have detrimental effects on the life of the operation and overall profitability.

Environmental Impacts: Airblast can also affect the natural environment. The force from the overpressure wave can disrupt wildlife habitats, disturb sensitive ecosystems, and potentially cause harm to wildlife species, particularly those with sensitive hearing. Most environmental legislation views noise as air pollution and has strict guidelines on the allowable levels of noise and exposure times within specified noise levels. As part of the global shift towards greener operations with reduced environmental impact through ESG initiatives, managing the blast-induced airblast has become more critical than ever before.

To minimize the potential impacts of airblast from blasting activities, the following mitigation measures can be implemented:

Blast Design Optimization: Proper blast design plays a crucial role in managing airblast and overpressure. By adjusting variables such as the explosive charge weight, timing, and initiation sequence, it is possible to control the intensity of the airblast and reduce the associated overpressure levels.

Buffer Zones and Setback Distances: Establishing buffer zones and setback distances between blasting operations and sensitive structures, or communities, helps to minimize the effects of airblast and overpressure. These zones provide a physical barrier that reduces the transmission of the blast energy to surrounding areas.

Pre-Blast Surveys: Conducting pre-blast surveys of nearby structures helps establish baseline conditions and identify vulnerable buildings or infrastructure. These surveys provide valuable information for assessing potential risks and implementing targeted protective measures.

Monitoring and Measurement: Continuous monitoring and measurement of airblast and overpressure during blasting activities are essential for ensuring compliance with regulatory limits and prompt identification of any exceedances. Seismic and air overpressure monitoring systems can be employed to track the intensity and propagation of the blast wave.

Communication and Public Awareness: Maintaining open communication channels with the surrounding communities and raising public awareness about blasting activities help manage expectations and address concerns related to airblast and overpressure. Providing timely information and updates can foster understanding and cooperation.

Engineering Controls: As with any risk-based approach, controls to mitigate the risks associated to blasting activities follow the standard hierarchy of controls namely, PPE, admin, engineering, substitution and elimination, with PPE being the least effective and elimination the most effective. It is, however, difficult to apply substitution and elimination controls for the majority of blasting activities and most operations therefore rely on PPE, and administrative- and engineering controls. When it comes to the control of the risk associated with the environmental impacts of blasting, mines and quarries have turned to technology to assist them in achieving optimised blasting outcomes whilst still operating within the legal limits of environmental impact. One such technology is the Varistem® stemming plug which has proven itself as an appropriate engineering control through various pilot projects and studies conducted. Varistem stemming plugs have successfully assisted mines and quarries to blast within legal noise limits, obtain more consistent readings and drastically reduce the overpressure from a blast. This is achieved through the Varistem® plug’s ability to add additional confinement to the blasthole and ensure the integrity of the stemming column is maintained which then ensures more energy is translated into the rock and less energy is ejected through the stemming column.

A Varistem pilot project was conducted at a South African opencast coal mine with the main objective to investigate if the Varistem® stemming plugs can effectively reduce the noise level reading and airblast generated from blasting activities. This study was necessary due to the proximity of nearby communities and schools which rendered the blasting zone as sensitive. This study included a total of 65 blasts in overburden and Midburden, of which 21 blasts used the Varistem® stemming plugs. The original blast designs (Table 4.) were not altered and therefore all Varistem® blasts had the same design parameters with the only difference being the addition of the Varistem® plug itself. A summary of the average of the noise and airblast data is indicated in Table 5.

Table 4: Blast Parameters at a Coal Mine

| Blast Parameter | Overburden | Midburden |

| Hole diameter(Production and presplit) | 152mm/165mm | 152mm/165mm |

| Burden | 5m | 5m |

| Spacing | 5m | 6m |

| Stemming height | 3.5m | 3.0m |

| Hole depth | 18.0m-20.0m | 18.0m-20.0m |

Table 5: Summary of the average of Noise and Airblast data at a Coal Mine

| VARISTEM® | NON-VARISTEM | |

| Number of blasts measured | 21.00 | 44.00 |

| Average actual Noise (dBL) | 121.36 | 129.98 |

| % Over USBM limit (>134dBL) | 4.8% | 13.6% |

| % Within USBM limit (<134dBL) | 95.2% | 86.4% |

| Average actual Air Overpressure (kPa) | 0.023 | 0.063 |

In this case study, the Varistem® stemming plugs yielded a reduction of 6.6% (±8.62dBL) in the average noise levels measured and a reduction in air overpressure generated of 63% (±0.040kPa) across all blasts monitored in this study. Also noted was an improvement of 8.9% in the number of blasts that measured within the USBM 134dBL noise limit.

An open pit platinum mine in South Africa has been experiencing challenges with the nearby community as they have been affected by the blasting activities carried out by the mine. Based on consulting a decision was made to conduct a 3-month trial with Varistem stemming plugs to investigate if the plugs can assist the mine in achieving lower noise levels and reduced airblast to mitigate the impact experienced by the nearby community.

The blast parameters used during the trial are indicated in Table 6 with the summary of the statistics relevant to the blast monitoring indicated in Table 7. The dataset represents 10 months, of which the last 3 months were the Varistem® blasts.

Table 6: Platinum mine blast parameters used in airblast trial

| Blast Parameters | Standard Design | Varistem® Design |

| Hole diameter | 127mm | 127mm |

| Burden | 2.5m | 2.5m |

| Spacing | 2.5m | 2.5m |

| Stemming height | 3.0m | 3.0m |

| Stemming configuration | Aggregate stemming | Aggregate stemming + Varistem® stemming plug |

| Hole depth | 10.0m | 10.0m |

Table 7: Summary of blast monitoring readings measured for a 10-month period at a platinum mine

| Data Summary | Min Noise (dB) | Aver Noise(dB) | Max Noise(dB) | Min AOP(Pa) | Aver AOP(Pa) | Max AOP(Pa) | Min PPV(mm/s) | Aver PPV(mm/s) | Max PPV(mm’s) |

| Without Varistem | 95.9 | 115.7 | 139 | 1.2 | 12.2 | 178.3 | 0.2 | 1.6 | 3.4 |

| With Varistem | 81.9 | 107.5 | 119.1 | 0.2 | 4.7 | 18 | 1.4 | 2.6 | 4.2 |

| Difference | -14.6% | -7.1% | -14.3% | -80.0% | -61.1% | -89.9% | 621.1% | 61.3% | 23.1% |

Figure 15 is a combination graph that depicts both the noise readings and vibration readings made at the mine during a 10-month window. The first 7 months were historic readings used as a baseline and the final 3 months indicate the readings from the Varistem® blasts.

Looking at the data in Table 7 and the graph (Figure 15) the following conclusions can be drawn:

Blast-induced noise, airblast and overpressure are significant considerations towards managing the impacts of blasting activities at mines and quarries. By understanding these concepts, the science behind them and how to implement appropriate mitigation measures, mining and quarrying operations can minimize structural damage, alleviate community concerns, and protect the environment. Blast design optimization, buffer zones, pre-blast surveys, monitoring systems, effective communication and engineering controls like the Varistem ®stemming plugs, play vital roles in ensuring responsible and sustainable blasting practices. By adopting these measures, the industry can strike a balance between resource extraction and environmental stewardship.

If you’re looking to reduce blast-induced noise, airblast, and overpressure, ERG Industrial’s Varistem® stemming plugs and expert engineering consulting services can help. Get in touch today to learn more about how we can support your operations with effective, sustainable blasting solutions.

Your choice of stemming plug is a significant decision for mining and blasting consumables. You might be fighting flyrock on sensitive benches, or trying to

In our business, we are in a unique position where we get to spend time at countless sites, working with drillers and blasters during the planning,

The purpose of the Varistem® stemming plug trial conducted at Coal Mine X was to reduce flyrock, noise, and airblast by retaining blast energy. The